Game Development with adventurelib + repl.it

A step by step approach to building a simple text-based adventure game

Create an account on repl.it

You must be at least age 13 or older to create an account on repl.it so if you aren’t then get a parent or guardian to create an account for you. Accounts are free and will allow code Python in a browser and also copy or fork example code into your own account.

To sign up, go here: https://repl.it/signup

It is worth repeating, but if offered any price plans when creating an account, always choose the free option.

About adventurelib

adventurelib provides basic functionality for writing text-based adventure games, with the aim of making it easy enough for young teenagers to do. This article is based on the excellent documentation that adventurelib provides and which you can access here: https://adventurelib.readthedocs.io/en/stable/index.html

Fork our Starter project

Our starter project really only has the bare bones including the adventurelib.py library which we’ll use to create our text-based adventure game but it should give you enough to understand how we use repl.it and how to run a basic game.

Click on the following link: https://repl.it/@CoderDojoBanb/adventurelibStarterProject

You will see a few things:

On the top left of the page, you’ll notice Files which shows:

main.py -> contains the code to run our game

adventurelib.py -> contains the adventurelib code that helps build our game

Along the top you’ll see two buttons. run & fork where fork performs the same function as Remix in Scratch, i.e copies the code into your account so you can change and modify your own copy. run _is somewhat similar to pressing the Green Flag in Scratch in that it will start your code running. Press fork now and it will take you to your own copy of the code in your account and then press run (you should notice that the _fork button is no longer visible after you press it).

On the right black screen you will eventually see something like the box below. Type ?, help and some other text to see what happens.

>

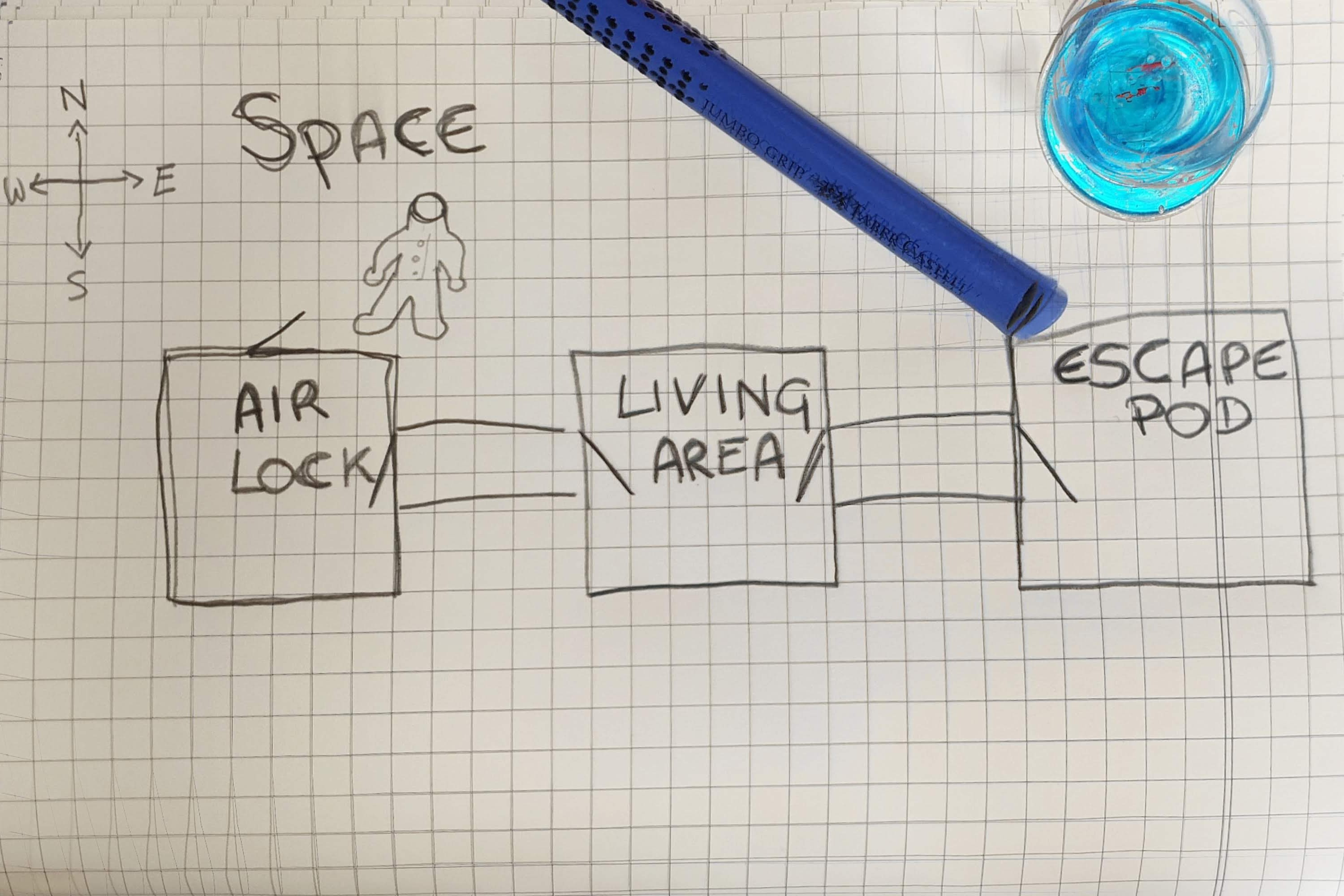

Grab a sheet of paper and draw a map

We’re going to be creating our own adventure where we’ll use text commands to navigate around the game, visiting a series of rooms. So, if you haven’t done so already, draw a map with 3 to 4 rooms. You could use rooms to describe any concept of location, in order to tell your story:

- Drifting in space

- Entering a spooky mansion

- On top of a hill

- Underneath the floorboards

- Nowhere

Here’s the one I’ve drawn to help me visualize the rooms my space adventure will take place in:

Think about how you’d describe each room and what elements would be in it?

Add a command

All of the rest of your code should go in between the from adventurelib import * and the start() lines.

Text adventure games respond to commands entered by the player. Some typical commands might be:

- north

- take wand

- give wand to wizard

We can use the @when decorator to create a command that a player can type in order to interact with your game, your code will then decide what happens when the command is issued. Let’s add a “brush teeth’’ command and use the say() function from adventurelib to output text in response:

@when("brush teeth")

def brush_teeth():

say("""

You brush your teeth. They feel clean.

""")

Try it out by running your code in repl.it Note that this is case-insensitive, so it will also be called when the player types “BRUSH TEETH” or “bRuSh TeEtH”:

If stuck, you can fork this working code: https://repl.it/@CoderDojoBanb/adventurelibAddCommand

Capturing Values

While you could write separate functions for “open airlock” and “close airlock”, it’s more normal to write a single function that will be called when the player types “anything airlock”.

This code will be called when the player types “anything airlock”, and the words that match the anything will be passed into the function so that you can react to what it was they tried to do to the airlock (Note: the words we are capturing are the ones in CAPITAL letters and there will be a corresponding argument of the same name but in lower characters passed to the function):

@when("ACTION airlock")

def airlock(action):

print(f"You {action} the airlock.")

So, in a game:

> open airlock

You open the airlock.

> close airlock

You close the airlock.

You can also capture multiple words, e.g.

@when("blast RECIPIENT with the ITEM")

def blast(recipient, item):

print(f"You blast {recipient} with the {item}.")

If stuck, try this completed example here: https://repl.it/@CoderDojoBanb/adventurelibCaptureValues

Rooms

As mentioned already, a room represents any location, inside or outside. You create a Room object by passing a description, so make sure it’s a rich evocative piece of text that helps tell a story and gives the player clues as to what can happen in there.

It’s also good to keep track of where you currently are, so we’ll use a current_room global variable (a global variable is one that is available throughout your program).

We’ll also place each room relative to each other, i.e. whether it is north, south etc of one of more rooms.

For my space themed adventure I’ll add two initial rooms:

# Define our current_room to be our starting room, i.e. space

current_room = space = Room("""

You are drifting in space. It feels very cold and you are alone.

A slate-blue space station sits completely silently to the south, its airlock open and waiting.

""")

# Define airlock relative to space, i.e. it will lie south of the previous room

airlock = space.south = Room("""

You are in an airtight room with two entrances that allows an astronaut to go on a spacewalk without letting the air out of the space station.

The walls of the room contain the space suits of your fellow astronauts.

""")

If stuck, you can fork this working code where we also have the living area and escape pod rooms in our space station: https://repl.it/@CoderDojoBanb/adventurelibAddRooms

Moving Between Rooms

We defined rooms but they’ve not played a part in our game yet. We need to allow our character to move around.

We could add a command for each direction, but let’s just use one instead and use a captured argument, direction, to see what the direction was. We’ll also need to change our global variable current_room to become the new room if we do change positions, note how we use global to make sure it’s the global version we use and not a new local version.

Finally we use the exit(direction) function from Room to do the moving. If no room exists in the direction we move then room will be empty and we won’t go into the if block:

@when('north', direction='north')

@when('south', direction='south')

@when('east', direction='east')

@when('west', direction='west')

def go(direction):

global current_room

room = current_room.exit(direction)

if room:

current_room = room

say('You go %s.' % direction)

look()

At this point it might be useful to describe the room we enter and for that we’ll add a new function look(). It is there on the last line of our go function but we’ve not defined it yet so let’s add it now:

@when('look')

def look():

say(current_room)

say(Room) prints out our description of the current_room. We will also add a call to look right before our start() line so that when the game starts you get a description of the room you start in:

look()

start()

If stuck, fork this code: https://repl.it/@CoderDojoBanb/adventurelibMoveAround

Items & Bags

Many games will allow players to pick up objects. Also perhaps some actions in the game will cause players to receive objects, such as when given them by a character.

To support this, adventurelib provides two classes that work together: Item and Bag.

Item

An Item can be used to represent a non-playing character or an object you can use in the game. In our game, a non-playing character could be a crew mate but for us we’ll add in a book of escape codes that we can use to program our escape pod.

escapes_codes = Item('book of escape codes', 'codes', 'escape codes', 'book')

The first name you give is the default name for the item, which can be inserted into strings. All the other names you give are aliases for the object.

Bag

A Bag is a collection of Items. This does not need to be a literal “bag” that the player is holding - it’s a metaphor! You could treat a Room as being a bag of items. Or a group of Characters could be held in a Bag. The point of a Bag is to allow you to look up items by the names that players have typed for them, letting you find, take Items from a Bag as well as being able to add items to it. Let’s add a Bag to some rooms as well as our player.

Room.items = Bag()

living_area.items = Bag({

escapes_codes,

})

pocket = Bag()

Let’s add a command to pocket those items:

@when('take ITEM')

def take(item):

obj = current_room.items.take(item)

if obj:

say('You pocket the %s.' % obj)

pocket.add(obj)

else:

say('There is no %s here.' % item)

Next we’ll update the look function to loop over the Items in a Room and print them out:

def look():

say(current_room)

if current_room.items:

for i in current_room.items:

say('A %s is here.' % i)

If totally stuck or confused, fork this: https://repl.it/@CoderDojoBanb/adventurelibBagsAndItems

Let’s add some randomness, Context and win/lose scenarios

Simply moving from room to room can be a bit dull, can’t it? Lets add a pinch of randomness! To use the random library, we need to import it and do so at the top of our code, as shown here:

import random

Let’s add a function that acts like a coin toss, returning true if heads, false if tails:

def cointoss():

return True if random.randint(0, 1) == 0 else False

Now we need to think where best to place this randomness. I’m going to add it to our living area and introduce a random chance that on entering the room, the space station is hit by a meteor. If that condition is reached, we’ll use set_context to add a command context as well which we’ll examine next:

def check_danger():

if current_room == living_area and cointoss:

say("""

Suddenly the station shakes as it is hit by space debris. A klaxon sounds, indicating the hull has been breached and the station will implode very shortly.

""")

set_context('danger')

Note: Add a call to check_danger() as the last line of our go(direction) function.

Finally, we want to have a command that will only be present and available in some circumstance. Enter that command context we mentioned above. We’ve set the context to danger and now we’ll add a function which will only be called when that context matches:

@when('enter code', context='danger')

def code():

if current_room == escape_pod:

obj = pocket.find('codes')

if not obj:

say("""

You knew you should have lifted that code book, but it's too late now as the station collapses around you!

""")

else:

say("""

You frantically pull the code book out of your pocket and key the correct code into the pod's computer. The pod slips away from the station just as it begins to collapse in on itself.

""")

exit()

We’ve covered a lot there, so fork this: https://repl.it/@CoderDojoBanb/adventurelibRandomContext